NOTE: Danish coverage of recent American events has been universally awful: whether on television, radio, web, or print, it’s all had the calm tone of MSNBC, the editorial equilibrium of the New York Times, and the penetrative historical insight of Vox. That is, it’s been a dumpster fire of unhinged and often uninformed hyberbole. Rather than go through particular lowlights and highlights (if there were any) of Danish coverage, I’ve decided to share my own thoughts and leave it at that.

Ashli Babbitt was shot and killed on Wednesday, January 6, while trying to climb through a window in the U.S. Capitol building.

Her death is another data point on the line we’re charting toward our destination, which doesn’t appear to be anywhere good.

An unthinkable tragedy became all at once not only thinkable, but possible—and then probable, and then suddenly inevitable.

A whole cascade of future unthinkabilities has become suddenly thinkable. How many of those formerly unthinkable things, now thinkable, will become possibilities? How many will progress through possibility to probability? How many future tragedies will trace their eventual inevitability to seeds being planted right now, by all of us, everywhere, without our even knowing it?

Not every acorn becomes an oak tree, but every oak tree began as an acorn.

The events of January 6th in Washington D.C. remind me of the Gabriel García Márquez novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold, which has one of literature’s great openings:

On the day they were going to kill him, Santiago Nasar got up at five-thirty in the morning to wait for the boat the bishop was coming on. He’d dreamed he was going through a grove of timber trees where a gentle drizzle was falling, and for an instant he was happy in his dream.

Chronicle of a Death Foretold, Gabriel García Márquez

Santiago Nasar is butchered by the Vicario twins despite the fact that everyone in the village, including himself, knows that he is going to be murdered. The telling of the tale takes us back and forth through time to illustrate all of the many ways in which Nasar’s death could have been avoided: the bad decisions, the quirks of circumstance, the bad luck. You know where it’s all headed, you want to shout “stop, stop!”—but it’s futile. One by one the choices are made, and with each one an entire set of alternative possibilities disappears. The logical progression of events moves on.

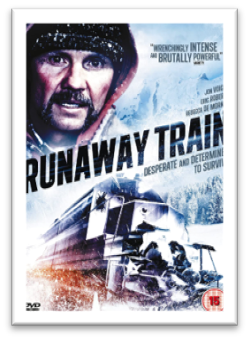

The train goes thundering along its tracks, accelerating toward its doom, and there’s nothing to be done.

It’s a feeling I’ve had for months. Years.

Ashli Babbitt is dead because she tried to climb through a window of the Capitol building alongside other rioters, some of whom were armed. A member of the Capitol police shot and killed her: whether the officer was targeting her specifically or simply firing into the mob hasn’t been revealed in any coverage I’ve seen.

Ashli Babbitt was a 14-year Air Force veteran and had, with Márquezian irony, once served in the Air National Guard unit known as the “Capitol Guardians.” Why was she committing such a felony? To ask is not to excuse: she was unarmed, but she was part of an armed mob committing a serious crime. (We’ll save the interesting law enforcement fatality reaction comparisons for another episode.)

Why was that mob of armed and unarmed men and women around her storming the Capitol in the first place? It seems likely to have had something to do with the certification of the November 3 presidential election planned for that afternoon.

Why would such a routine and bureaucratic exercise excite such fervor? Surely in part because the president they supported was still suggesting, absurdly, there was a chance of somehow preventing the certification of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris as the next President and Vice President of the United States. But also in part because they believed that Donald Trump had been the rightful victor of the November 3 election, a belief the president very obviously, loudly, and frequently shared.

Why would anyone—the president, Ashli Babbitt, the mob, anyone at all—why would anyone believe that an American presidential election had been stolen?

It is tautological that no one could hold such a belief without having lost all confidence in the American political system from root to branch. It is equally tautological that sustaining such a belief would be impossible for anyone with faith in the establishment media, which declared Biden the victor on November 7 and spent most of the time from then until Wednesday, January 6, explaining that the election had been legitimate and without widespread fraud and that Donald Trump was wrong to challenge it (and that Democratic challenges to presidential elections in the past had been different). Such a belief would also be impossible for anyone with faith in the world’s largest social media, where users were flagged and even banned for suggesting there had been anything at all illegitimate about the election or that Donald Trump would have won if not for various irregularities.

How could such a large number of people have lost so much faith in the American political system, the news media, and the world’s largest and most influential social media platforms?

Here we cross paths with another interesting set of questions, which is merely the implied obverse of those just posed: how could such a large number of people spend four years insisting that Donald Trump had only become president by manipulating our political system with help from Russian interests, if not Vladimir Putin himself, and that extraordinary measures were therefore justified in removing him from office by any means necessary, only to turn around on a dime and insist that the American political system was incorruptible, and that merely to question its integrity was beyond the pale? How could so many men and women in the establishment media perform the same mental reversal? How could anyone who believed that a system corrupt enough to let Donald Trump cheat his way into the presidency suddenly, after four years of control by a man who had exploited that corruption to seize the presidency, purge itself of all taint and become incorruptible?

How, in fact, can two halves of the same country come to hold such wildly conflicting views about the most fundamental operations of their republic?

When we are so plainly and obviously and radically divided, it may be a mistake to look at either side of the divide to determine who’s right and who’s wrong: both sides are surely right on some thing and wrong on others, but if we want to understand whether that divide can be bridged we need to take a wider view.

Let’s forget “sides” for a moment and see where we are:

The election of Joe Biden in 2020 provoked claims of massive voter fraud and cries for extraordinary measures to overturn the election results, and ultimately a riot in Washington, D.C., and the storming of the Capitol.

The election of Donald Trump in 2016 provoked claims of massive election interference and cries for extraordinary measures to overturn the election (either because of Russian interference or simply to block Donald Trump from the White House), and years of law enforcement and intelligence investigations into the means by which Trump stole the election.

If we set party aside for a moment and speak only of Americans, then we can say that distrust in the integrity of our political process crossed a threshold in 2016, and that the trend accelerated in 2020.

Why are Americans losing the willingness to concede political defeat? Is the machinery of our political system so riddled with corruption that our presidents are those most adept at manipulating its filthy levers? Or have we simply lost the virtue of accepting defeat gracefully?

Or is it something else entirely?

American Democrats are quite comfortable in their beliefs. So are American Republicans. When we count noses, the country is almost evenly divided between the left and right.

Our problem, as I see it, is that those noses are not dispersed uniformly across geography and industry.

The nation may be evenly split, but most of our largest cities are at least 60:40 left to right and most of the rest of the country is at least 60:40 right to left. Various studies by various groups of varying political allegiance put the percentage of journalists who are Democrats at 65-94%. The most comprehensive study of its kind on academics identified only 9.2% of full-time faculty members describing themselves as conservative (that’d be a 91:9 ratio). And we don’t need studies to identify the political allegiance of “Big Tech’s” captains of industry: the chief executives at Apple, Google, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube have all made their political sympathies quite public. The entertainment industry is also overwhelmingly openly and proudly leftist.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with that on a case by case basis. Being a Democrat doesn’t mean you can’t be a fair journalist, or professor, or titan of industry. Political partisans can act, direct, sing, compose, and write to universal appreciation.

I wouldn’t care, and I doubt any conservatives would care, if journalists were 100% in the tank for the Democratic party if only their work product didn’t so obviously reflect that. If, for example, our leading primetime anchors were uniform in their treatment of the people and issues in the news. And I don’t think we’d care about the political orientation of university faculties if their curricula didn’t reflect it so flagrantly. Nor would conservatives give a damn who a Jack Dorsey or Mark Zuckerberg voted for or donated to if their companies were even-handed in their treatment of Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, collectivists and individualists.

The one industry that seems to have managed that feat even a little bit, to my perpetual surprise, is Hollywood. While it’s true you won’t see many Hollywood movies with explicitly conservative themes (that aren’t directed by Clint Eastwood, in any case), and while there’s plenty of leftist propaganda embedded in plenty of movies, Hollywood still manages to make movies that can be enjoyed by conservatives. Yes, I know, they still cast Republican characters as ridiculous caricatures of the liberal idea of a conservative (Richard Dreyfus does this with palpable glee in The American President), but I have no doubt that more conservatives enjoy Hollywood movies than enjoy CNN or the New York Times, or than could abide even fifteen minutes of a typical Woman’s Studies course at an ivy league university.

So the problem isn’t the imbalance in these industries and institutions, but in the group-think it perpetuates. Not even in that group-think per se, but in how it manifests itself. When everyone around you sees the world as you do, when your colleagues and superiors and subordinates are all in virtual lockstep on most political and social questions, when your big intramural battles consist of Democrats arguing with Socialists, then your objectivity is inevitably going to be dulled (if not entirely erased), and that’s going to show up in your product.

This is a phenomenon that’s been underway a long time. I don’t know why: there’s nothing about journalism or academia or entertainment or tech that suggests it’s best served being staffed by liberals. But the why isn’t meaningful right now: the what is what matters, and there’s no question that these territories are entirely occupied by leftists who have become entirely comfortable letting their politics color their professional work.

From its very dawn, American broadcast news was owned, operated, and staffed from what we might call a corporate liberal perspective, even as America itself was and remained a politically conservative country. It wasn’t so much a question of our prime-time anchors—men like Edward R. Murrow, Walter Cronkite, David Brinkley, Chet Huntley, Dan Rather, Ted Koppel, John Chancellor, Peter Jennings—being openly hostile on camera to conservative politicians and policies, or openly supportive of those on the liberal side, as a question of editorial selection and framing: which stories got prominence, which got buried or ignored; which personalities were interviewed, and what kinds of questions were asked—and what kind of answers were accepted from whom. Americans have bickered over the extent of this bias, and the scope of its impact, for decades, but the specifics aren’t relevant here: what matters is that conservatives felt it keenly. Even if there was no actual bias of any kind, even if the very idea of news media bias was entirely imaginary, conservatives believed there was, they perceived themselves being treated differently by the broadcast news media than liberals were, and the evolution of American mass news media since the 1980s has in large part been driven by that fact. Whether it was an accurate observation of a real phenomenon or a mass delusion is beside the point. Up until the late 1980s, the broadcast news on ABC, NBC, and CBS were the only game in town (Americans could also get their news from PBS on television, and NPR on radio, but relatively few did). Conservatives could grouse and grumble, and they did, but life went on. And then on August 1, 1988, something inevitable happened: a small-market radio host who had tapped into this ignored market segment went into national syndication. It changed everything.

His name was Rush Limbaugh and he was an unrepentant conservative. If you’ve heard of him, you probably know what an obnoxious and uninformed loud-mouth he is, how crude and ignorant and racist and misogynist and yada yada yada. If you’ve ever actually heard him, however, you probably understood why he quickly became a sensation. For one thing, he had stepped into an absolute vacuum: never before had right-of-center Americans heard someone articulating their beliefs so loudly and clearly on a nationally syndicated program (William F. Buckley’s Firing Line was an important exception, but Buckley never really had the popular touch). I say this with the authority of personal experience: the first time I heard Rush was in 1989: I was a young conservative living in Hollywood—“fish out water” doesn’t begin to do it justice—and stumbling across Rush on my car radio was a revelation. Here was a man who saw the world as I did, whose point of view aligned with mine, and his voice was coming at me from an establishment radio station: it was the first time in my adult life I’d experienced that. There’d been plenty of conservatives on little local radio stations across the United States, as Rush himself had been in Sacramento: what made Rush different, what got him syndicated and kept him syndicated and allowed him to change the actual cultural landscape of American politics, was that he was entertaining, and smart, and well-informed, and funny, and blithe. He was, in a word, riveting. He was also a shot across the bow of the monolithically liberal American mass media landscape. It was still in the late 1980s, remember, so there was no internet, cable was still finding its legs, and “mobile phones” cost a fortune and weighed about two kilos. The establishment media had been exclusively liberal for decades.

In January 1955, a Democrat Majority was sworn into the House of Representatives. That was not an unusual occurrence at the time: over the previous two decades (1935-55) there had only been two two-year Republican majorities. But over the thirty-eight years from that 1955 day all the way up through the start of Bill Clinton’s first term in 1993, the House of Representatives remained in Democratic control without interruption. Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford, Carter, Reagan, and Bush 41 never had anything but Democratically-controlled Houses.

Apart from the first six years of Reagan’s presidency, the Senate had also been run exclusively by Democrats from 1955 through Clinton’s first term in 1993. Congress was, essentially, a Democratic institution.

In the general election of November 1994, both houses flipped to Republican control. In only four of the past 26 years have Democrats regained control over both houses of Congress (a control they have just retaken for the next two years).

In a December 1994 article in the Times, Katharine Q. Seelye noted (with the usual leftist condescension):

[Rush] may have relentlessly promoted the “Contract With America” — the Republican campaign agenda — and trashed the Democrats all fall on his 659 radio stations and 225 television stations, but, he said, he was merely “validating” a feeling already abroad in the land.

A less partisan way of wording that nasty bit of work might be, “Rush’s relentless promotion of the Republican ‘Contract with America’ may appear to have been the key to their victory, but he believes he was only reflecting the feelings of the electorate.”

Indeed, Ms. Seelye quotes several politicians crediting Rush with the win. But she also quotes him more extensively—note how prophetic his words have turned out to be in retrospect:

Later, he addressed the [Congressional] freshmen and declared himself “flattered beyond my ability to express it.” He said: “For me to sit here and actually think I had some serious, profound role in it? You are the ones who took the risks. You are the ones who ran for office,” raised the money and took the heat. He added, “I’m just a media guy.”

Mr. Limbaugh told the freshmen that if they stayed “rock-ribbed, devoted, in almost a militant way to your principles, you will continue to be sent back here until you’re term-limited out.”

But he warned them that the press, which he called “willing accomplices to the liberal power base in Washington,” was preparing to investigate the Republicans because the new majority “upset the apple cart.”

He also advised: ”Say what you believe, with passion and bravado, and you’re going to offend half the people who hear it,” but that is the mark of effectiveness. He said that Democrats were misguided in trying to find a liberal talk-show host to counter him. “They haven’t figured out that it’s their ideas that beat them,” he said.

His impact and importance simply cannot be overstated. He revolutionized American radio and the phenomenon of his success shone a light on the largest and most underserved niche in the wealthiest consumer market in the world. He helped the Republican party take control of Congress for the first time in four decades. When you look at it that way, it’s astonishing that eight full years elapsed from Limbaugh’s premiere national broadcast to the launch of Fox News in 1996.

If Rush’s own popularity was a symptom of an already rightward-shifting electorate, as he himself seemed to believe, it further emphasizes how badly out of touch the major broadcast media had fallen with respect to their audience.

Newsroom bias was a topic of conservative discussion before Rush came along, and it remained a prominent subject through the 1990s, even as Fox new made its debut and the toddler internet began its celebrated disruptions—most pointedly with a hitherto obscure news aggregating website and newsletter run by the twenty-something manager of the CBS Gift Shop in Los Angeles: Matt Drudge. Drudge almost single-handedly blew up American politics in 1998 by bringing President Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky to national attention. Clinton’s serial infidelities had until then been the best-known secret in Washington, but the liberal media hadn’t touched it.

Even so, until the 2001 publication of Bernard Goldberg’s Bias the very notion of liberal bias in what was by then being called the “mainstream media” was still waved off by everyone else as conservative sour grapes.

With the publication of Bias: A CBS Insider Exposes How the Media Distort the News, which instantly became a New York Times #1 bestseller, “waving it off” became something more like “deliberately ignoring it.” Goldberg had served nearly three decades as an award-winning reporter and producer for CBS (one of America’s three broadcast networks) and the Democratic establishment would have done well to heed his warnings. Conservatives who thought they had finally found a champion for their cause of media criticism were quickly disappointed, however, because rather than take Goldberg’s criticisms as an opportunity for some soul-searching and reform, most political liberals and media professionals (but I repeat myself) simply dove head first into the Goldberg-bashing game.

It may not be possible to establish the relationship between the growth of new media and the increasing partisanship of America’s legacy news media, but there’s been a certain symbiosis between them over the past quarter century, and a lot of the toxicity of the current national “conversation” is a direct consequence of it. When in August of 2016 the New York Times ran a front page column declaring that journalistic standards made objective campaign coverage of the 2016 election impossible, they were only saying out loud what most honest observers already knew: the Times was a partisan news organization. Like the Washington Post. And the Los Angeles Times. And the Boston Globe. And ABC, CBS, NBC, PBS, CNN, and MSNBC.

(The very organizations that Danish media rely upon for their own political reporting on America.)

The purpose of that digression into the evolution of conservative news media in the United States was to illustrate its inevitability. Politics isn’t any fonder than nature is of vacuums: Rush Limbaugh filled a void and was eventually joined by Fox News, and Matt Drudge, and all their eventual successors and copy-cats. The question a sober observer should ask is not “where did these right wing people come from?” but rather “why was there such a vacuum in the first place?”

(That’s yet another question for another day.)

The point is that the void was filled, so that instead of a monolithic news media that reflected the political and philosophical diversity of the American public, we’ve ended up with a bipartite American media universe, each side of which is politically and philosophically homogenous.

There are signs that pattern is starting to be replicated in education and tech, and there’s no reason not to think it will play out in entertainment as well.

We are actively and even eagerly self-selecting into like-minded camps. We have been doing it for decades. There is nothing accidental or unintentional about it. Choice after choice has been made, step after step has been taken down this road.

Ashli Babbitt was shot and killed on Wednesday, January 6, while trying to climb through a window in the U.S. Capitol building because the foundational American idea, the corner stone of our republic, our very motto, has been willfully discarded. E pluribus unum has become e pluribus duas: from many, two.

There are still choices to be made, circumstances to play out, and dice to be tossed. It may still be possible to force newly thinkable things back into the box of unthinkables. But the distance to disaster is shortening.

And it doesn’t look like our incoming president is going to be any better at uniting us than our outgoing president was (although at least he’ll have the support of “his” media to tell us he is).

Indeed we could, and we did. The nation just witnessed months of rioters, insurrectionists, and domestic terrorists whom we were repeatedly told were mostly peaceful protestors.

And let’s not pretend that D.C. real estate is somehow sacrosanct: the Kavanaugh confirmation hearings of 2018 haven’t been entirely flushed down the memory hole yet.

Let’s hope time is unkind to my assessment.

I really do hope that Joe Biden is the unifier he claims he wants to be, rather than a talker of unity that rolls out the same old partisan approach to everything.

I really do hope the Democrat-controlled Congress will pursue a path of civility rather than one of vengeance.

I really do hope our monolithic leftist media can open itself up to more heterogenous perspectives.

I truly hope that social media will recognize the boundaries they’ve overstepped and take significant steps to become the neutral platforms they claim to be.

And I truly hope our institutions of higher learning can begin returning to their mission of education rather than doubling down on indoctrination, so that we can avoid the otherwise inevitable rise of a parallel universe of “conservative” American educational institutions.

I’m not holding my breath.

But unless and until those hopes are realized, the conservatives frozen out of politics and establishment media, whose voices are squashed on social media and university campuses, will have no choice but to continue creating their own parallel culture.

And the train will keep rolling.

Greg–

You keep saying you want responses, however you apparently don’t want to respond yourself to responses–or perhaps just those that don’t fit your preconceptions. Regardless, here’s another one, a link to today’s post regarding the ongoing events in the US from perhaps the most insightful and incisive analyst of what’s going on in the US these days, Heather Cox Richardson (author of “How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America”–which I suggest you also read). She does daily analyses that you might find useful–that is if you’re truly interested in understanding your country-of-origin.

Be well~

https://heathercoxrichardson.substack.com/p/january-10-2021?utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=cta

Hi John!

I think you’re reacting to the blog’s automated comment-begging bot, not me personally, when you say I “keep saying that I want responses.” It’s an automated thing that just happens. I am indeed happy for all responses, but it’s the bot that’s annoying you (and me) while you (and I) read. I’d disable it, but until there are more readers and more comments it doesn’t seem like such a bad idea to let that little sucker buzz around. (Although I’m not so keen on the idea that people think I’m watching them read the blog in real time and poking them while they read. Maybe I can figure out how to change the text of that thing.)

I don’t know what you mean when you say I don’t want to respond to my responses, though. From what I can see I haven’t neglected any comments. I haven’t worked with this comment system before, so possibly I’m missing something, but I’ve responded to every comment I can see from the “Comment” control panel except for this new one from you that I’m responding to right now. So as far as I can tell, I’m batting a thousand. If there’s a particular comment you can see that I haven’t answered, please let me know!

I obviously therefore have no idea what comments you think I’ve neglected, or what those omissions would suggest about any of my preconceptions, and I find it strange that anyone who’s spent more than a moment on this blog, which you obviously have, would imply that I’m not “truly interested in understanding [my] country of origin.”

If there’s something in this (or any) particular post you dislike or want to call me out on, fire away! State your case in your own words, make your own arguments, tear my own ideas to shreds, tell me where I’m wrong so I come out of the exchange wiser than I entered it. (Or you do, or we both do.) I love a good clean debate. That’s fun and engaging and probably interesting for other people to read. But if you just pop up to tell me you think I’m ignoring comments and need to improve my own understanding of America by reading a writer you’re fond of, that’s not really fun or engaging.