The forthcoming Danish election is sucking up most of the oxygen in the Danish press these days, for obvious reasons. I haven’t been giving the election a corresponding level of attention in this blog because first of all this isn’t a blog about Danish politics per se, and secondly because the vast majority of readers are visiting from outside Denmark and therefore need a lot of context and backstory before they can begin to be interested in such things.

I’m a lazy man, in many ways, and just don’t have the wherewithal to provide the necessary background every time I want to make an observation about the election. Hence the lack of observations.

There are, however, generalities that can be discussed without relying too heavily on specifics.

One of those is the attempt to create a “purple” government consisting of a parliamentary majority made up of parties from both sides of the political divide.

Before I get into that, here’s an oversimplified primer on the state of play in Danish politics right now.

An Oversimplified Primer on the State of Play in Danish Politics Right Now

In Denmark as elsewhere, the political landscape is divided almost evenly between the right and the left. There are fourteen (14!) parties on the ballot, representing a wide divergence of ideologies. The dominant party of the left is the Social Democrats (Sociademokratiet). The dominant party of the right had for decades been the Liberals (Venstre), but that party has recently been hollowed out by a variety of new parties on the right. The current government is a leftist coalition with the Social Democrats wielding most of the power.

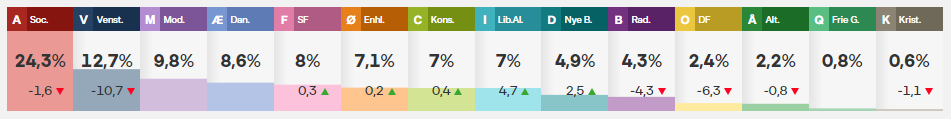

In current polling, the Social Democrats have the support of 24.3% of the electorate. The Liberals are a distant second with 12.7%. In third place are the Moderates (Moderaterne) with 9.8%.

The Moderates are a brand new party started up by Lars Løkke Rasmussen, a man who has already been prime minister twice as a Liberal. The Moderates seek to assemble a purple coalition—with Lars Løkke Rasmussen as PM.

In an electorate where the biggest party can only garner about a quarter of the votes, any government will necessarily be a coalition of parties comprising more than 50% of the electorate—or, more accurately, more than 50% of the seats in parliament.

When you look at how things stand right now, you can see there are a lot of ways of getting to 50%:

What you probably can’t see, unless you already understand Danish politics very well—in which case you could have just skipped this whole oversimplification—is that it’s very difficult to find a way to get to 50% that doesn’t include the Moderates or require at least one party to cross the aisle.

On the left, A + F + Ø + B + Å + Q = 46.7%.

On the right, V + Æ + C + I + D + O + K = 43.2%

And then you’ve got the Moderates with 9.8%, more than enough to give either bloc a majority.

It’s a little more complicated than that, because parties have to achieve a threshhold of support to win a seat in parliament: neither Q nor K would get a seat in parliament as things stand today.

There are 179 seats in the Danish parliament: 90 are therefore required for a majority.

On the left, A + F + Ø + B + Å = 82 seats.

On the right, V + Æ + C + I + D + O = 75 seats.

The Moderates would get 18 seats.

Got it?

One More Thing

If you’re the sort of person that can’t help doing math in your own head, you will have noticed that the seats tallied above only add up to 175. That’s not because I’m bad at math, but because it doesn’t count Greenland or the Faroe Islands, each of which has two seats. Of their combined four seats, three are expected to support the red bloc of the left. That brings the left to 85.

Only a few days ago it looked like the red bloc might have 87 seats, meaning the three from Greenland and the Faroe Islands would allow the red bloc to remain in power without any help from the Moderates. That no longer appears to be the case, but things are fluid.

Moving On

One of the great themes of this election is therefore what kind of coalition is likely to come out of it. That’s the great theme of every election, obviously, but it’s more confusing than usual this time around. The parties of the right and left are being subjected to conflict from their own members as to whether or not they should be willing to join a Moderate-led coalition as part of a Rasmussen government, and, given the nature of this mess, parties are being pressured by their supporters to make it known which parties from the other side they would and would not be willing to work alongside in a purple government.

Without getting into specifics, which would only make your eyes glaze over, suffice to say there are particular parties on the left who find particular parties on the right absolutely intolerable, and vice-versa. All the parties appear to have a lot of members who disagree quite strongly with their leader’s statements on whom they could and could not work with.

The three parties that would almost have to be involved in any purple coalition are the three that are leading the polls: the Social Democrats, the Moderates, and the Liberals. They hold 46.8% of the electorate in their hands: any of the seven next-largest parties would be enough to make them a majority coalition.

But let’s drop all the math and all this talk about coalitions and partnerships and grudges and talk instead about what actually matters: how would a purple government under Lars Løkke Rasmussen actually govern?

Would it? Could it?

There’s a conservative case to made for a government so paralyzed by internal contradictions that it can only take action on the most necessary issues with the broadest support. Such a government would therefore accomplish very little, if anything, beyond what it absolutely had to. There are many conservatives, myself included, to whom that would be a refreshing change of pace.

Believe it or not, however, there is also a conservative case to be made for conservatism.

Shocking, but true.

When I cast my ballot for one of the blue bloc parties, I’m casting my vote for a very specific set of ideas and beliefs. I want taxes lowered significantly, I want the public sector scaled down, I want a commitment to reliable energy independence and an end to green hysteria, and a whole bunch of other things besides. None of those are going to be possible if they require the consent of the welfare-state environmental extremists dominating even the most “centrist” of the red bloc parties. (Most of them aren’t even supported by a large swathe of the ostensibly conservative blue bloc.)

My collectivist friends on the left presumably feel the same way: they want more green hysteria, more money spent on renewables, higher taxes, and a bigger government handing out more benefits—not some treacly half-assedness borne of compromise with idiots like me.

It brings to mind Chesterton’s “paradox” of globalists: that if you want real globalism, then it’s no good getting the globalists of the world to agree on things. Real globalism can only be achieved when the nationalists of the world forge an agreement.

In the same way, declaring oneself a “moderate” is an empty and cynical ploy. You don’t get compromise from people pledging their unyielding support for moderation but from agreements hammered out between people who are fiercely committed to wildly disparate points of view. Standing athwart the center shouting “compromise!” is as stupid as it is superfluous. All politics is compromise—”the art of the possible,” as Aristotle defined it.

Lars Løkke Rasmussen is running on “compromise,” which is to say nothing at all. Go ahead and read the page of the Moderates’s website that attempts to answer the obvious question, “Why vote for the Moderates?” It’s a big ball of mush. Take the opening line:

The Moderates is founded on a humanistic value base and with an ambition to contribute to a political culture where the focus is on content, substance, and evidence rather than process, symbols, and loose assumptions.

Well sign me up, spanky, because I’ve been longing all my life for a political party with an ambition to contribute to a political culture where—

Wait, I just stubbed my toe on the subtext: if you’re running to create a focus on content and substance and evidence instead of “process, symbols, and loose assumptions,” aren’t you suggesting that the political opponents among whom you hope to engender compromise are focused on all that crap you want to get away from?

And isn’t the insinuation that the other parties are sleazy opportunists operating in bad faith exactly the kind of crap you’re supposedly running against?

And just how much compromise do you expect to elicit from the parties you’re accusing of not being as interested in content, substance, and evidence as yours?

But go ahead and read their full statement. As a friend noted recently, the Moderates would at least solve Denmark’s energy crisis on the sheer volume of gas they’re providing.

The center of politics is as hollow and formless as the center of a bagel or a donut: it’s the empty place surrounded by all the actual substance.

And Denmark seems poised to elect its first donut-hole government.