The so-called “Law of Unintended Consequences” doesn’t have a definition because the name of the law is the law: there are always unintended consequences.

You kick a stone out of your way as you hike up a mountain trail—and inadvertently start an avalanche that buries a small town.

You flick a cigarette out the window of your car—and start a wildfire that destroys thousands of acres of forest.

You go on a canoe trip with a good friend and end up with two kids and a mortgage in a country you probably couldn’t have found on a map. (It happens.)

Every reference to the Law of Unintended Consequences is just an acknowledgement that there are unintended consequences. It’s a polite way of saying shit happens.

And shit certainly does happen.

There is no universal fact of human social existence we ought to be more attentive to than that simple maxim.

Everyone knows that everything they do is going to have consequences. We know that some consequences will be immediate and some won’t manifest themselves for weeks, months, or years. We know that some can be expected, some are possible or probable, and still others are entirely unforeseeable. We know that some will be to our advantage, some we’ll hardly notice, and some could come around and bite us in the ass.

We factor those considerations into our decisions a thousand times a day, from little things like what we have for lunch and how we cross the street all the way up to the biggest things of all, like whom we choose to marry and when to have children.

But all that contemplation and foresight goes right out the window when it comes to public policy.

We’re all too often all too ready to accept the promised benefits of every proposed solution without giving much (or any) thought to any of the many possible negative consequences (unless it’s something being proposed by a political adversary, in which case of course it’s negative consequences all the way down).

We accept cash handouts from our government with glee—without reflecting that the only money our government has to hand out is the money it’s requisitioned from us.

We cry out with compassion for refugees who seek shelter in our countries and invite them in by the millions—without reflecting on the burden they’ll be on the social systems we rely on ourselves.

And we shut down schools to prevent the spread of a virus that poses little or no danger to children—without reflecting on what that will do to the children.

Something worrying has happened with children in Østerbro and Gentofte—”They’re behaving in ways we haven’t seen before”

Rasmus Karkov, Berlingske.dk, November 26

It’s a long article—and worth reading in its entirety, even though it’s as depressing as it is long.

The headline tells the story, and it’s a story anyone with school-aged children hardly needs to be told.

We fucked up our kids.

As the article makes clear, it’s hard to say exactly how the damage we’ve done to them is going to manifest itself: it’s early days yet. But the signs of that damage are evident to everyone: parents, teachers, counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, police, social workers—even journalists.

We have one job as adults: produce the next generation.

Given the amount of time it takes for a human child to achieve maturity (about 16-18 years for females and 60-70 years for males), “producing” the next generation goes well beyond the mere act of reproduction. We have to civilize the little barbarians, we have to care for them and tend to them and instruct them, in order to ensure the survival of our species. Even the childless bear some responsibility for ensuring the next generation is prepared to take the human adventure just a little further down the line. We’re a species, we need to survive. Everything else is just window dressing.

When this virus came along we knew very quickly that it was most lethal on people who were very old, very sick, or very fat. The mortality stats were suggesting as much by the end of March 2020, and it was a certainty by the end of April.

And to protect the very old, the very sick, and the very fat, we threw our kids under the bus.

All our kids.

I know that sounds hyperbolic, but it sounds even more sinister when I try to phrase it as neutrally and accurately as possible: we subjected all of our children to conditions whose consequences we could not predict in order to protect people to whom that protection was not known to be necessary or sufficient.

It didn’t make much sense, but to raise your voice against it—to merely question it—was considered inhumane, hateful, and inflammatory. Even murderous.

And now we’re beginning to recognize what any idiot could have told us back in the spring of 2020: lockdowns and school closures would have consequences on our children.

As indeed they did.

And we may not yet fully understand the consequences, but we do seem to finally coming to terms with the fact that virtually none of them are good.

We didn’t damage our children by ignoring the experts: we damaged our children by neglecting to question the experts. By not pushing back. By allowing questions and pushback to be stifled.

That obviously opens things up for a broad panorama of questions about the nature of authority and authoritarianism in 2022, for example—but that’s not where I’m going with this.

I’m sticking with the children and our responsibility for their welfare and another set of unintended consequences we completely ignored (or stifled, or allowed to be stifled)—with a separate issue that I suspect we may eventually find is tangled up with the issue we began with.

It’s actually hinted at in the article:

At SSP [Schools, Social Services, and the Police, an organization dedicated to keep kids out of criminality], in the youth clubs and at the schools, they find it difficult to put their finger on exactly what the difference is. But something is different with the children who, in their formative years during the corona lockdowns, were sent home for the longest time of all, and who are now 13-14 years old.

It is not a uniform difference. There are variations. But in the end it might come down to what chairman of Danish School Students, 16-year-old Marie Holt Hermansen, says in her frantic tone:

“We are probably a youth generation that has become more rootless.”

For some, it’s empty afternoons in the room, where loneliness inevitably takes hold, when there’s nothing more to kill time with on TikTok.

For others, it’s alienation. An infinitely sad realization of having experienced social isolation in the years when you most need to mirror yourself in others, which no parents or teachers will ever be able to understand.

Perhaps the closest thing—without comparison, by the way—were the disillusioned young adults who, exactly 100 years ago, in the roaring 20s, drank in the First World War and the horrors of the Spanish flu from a distance because they knew the world could change in a moment.

They went by the name The Lost Generation.

The deepest fear is that we now risk losing parts of a generation that missed out on too much for too long.

Never mind all the drama, just note two things: we’re talking primarily about 13-14 year olds and we’ve name checked TikTok.

It didn’t have to be TikTok: it could have been Snapchat or Instagram or any other social media.

These 13-14 year olds weren’t just the guinea pigs for our global experiment with school closures and lockdowns: they also happen to be the first generation in human history for which touch-screen “smart devices” have always been a part of life. The first generation to grow up with the world in their pockets. And on their nightstands.

After all, they were born in 2008 and 2009, just as iPhones and iPads were beginning to saturate the market. In wealthy western nations, many of these kids—probably most of them—were using touch-screen devices before they were being socialized in daycare or nursery school.

Eldest was born in 2004 and Youngest in 2008: Eldest had to learn how to use the mouse on the one computer we had in the house to watch her favorite video over and over (and over) again, because Mor and Daddy would only allow seven or eight repeats:

Where was the harm?

By the time her little sister arrived, iPhones were on the market, and iPads came shortly thereafter.

Youngest was playing games on the family iPad and her parents’ iPhones while she still just a toddler.

She was learning so much! Shapes, and colors, and songs, in English and Danish, and all sorts of wonderful things. What a boon to pedagogy these new devices were!

Thanks to those devices they grew up in regular face-to-face communication with family members who lived three thousand miles away.

By the time Eldest was entering 7th grade, smart devices were ubiquitous. She had her own smart phone—an old one of mine, locked down pretty tight, parental controls up the wazoo—and Herself and I did our best to check it frequently to make sure she wasn’t doing anything she oughtn’t to have.

“Don’t ever send anyone naked pictures of yourself” wasn’t advice my parents had ever had to impart to me or my sister, but Eldest heard it from her mother and me so often we may as well have tatooed her with it.

Even so, bad things sometimes happened.

One day I heard shrieks of anguish coming from Eldest’s room—from the sound of it I was sure she’d either hurt herself horribly or spotted a spider the size of a Volkswagen. I ran to her room in a panic, and she was holding her phone at arm’s length and sobbing.

“What do I do? Make it stop, make it stop, what do I do?”

A boy in her class had logged into Snapchat or Instagram as her and was commenting as her on the posts of all the other kids in the class: “I love Mathias so much, he’s so cute” and “You look dumb in that picture, Emilie.” Stuff like that. Which was, in her totally wired world of junior high school, obviously traumatic.

We watched together for a moment as more and more of “her” comments got posted. The little shit doing all this was prolific.

“Who’s doing this?” I asked. “How?”

She said she’d given one of the boys in her class her password for some idiotic reason and now he was abusing it.

I immediately guided her through a quick password change.

No sooner had we changed the password than the phone pinged as an incoming message came in from the very same boy.

“Give me your new password now!” his message said.

The phone was in my hands.

“This is her father,” I replied, “stop what you’re doing right now and expect to hear from your parents.”

That stopped the comments—and confirmed the identity of the boy.

I then looked up the email address of the boy’s parents and sent a message telling them what had happened. I said he owed Eldest an apology and should also let everyone in the class know it had been him, not Eldest, posting all those comments.

You won’t believe what happened next!

The little shit’s father wrote back and told me that Eldest had just let his son “borrow” her password “so he could see her pictures,” and so he didn’t see that he had anything to apologize for. And that was that.

The man hadn’t understood anything at all I’d told him, didn’t understand what his son was doing on social media, didn’t understand social media, and obviously didn’t care.

Just recounting that story again after all these years makes my blood boil all over again.

And that’s one story from one household on one evening.

So when SSP came by Eldest’s school to meet with parents and talk about all the challenges facing our kids at their vulnerable age—peer pressure, alcohol, drugs, cigarettes, sex—eventually the topic of social media came up and I raised my hand.

“Is anyone thinking maybe our kids shouldn’t even be on social media at all, and maybe not even have these smart devices until they’re older?”

The SSP guy smiled patiently. Clearly I fit the archetype of some kind of parent he was always having to deal with.

“These devices are out there,” he said. “That’s just how the world is. We have to accept it and work with it.”

Too many other parents nodded along in agreement; my courage collapsed.

Only after the meeting did I realize that we’d talked about how to keep our kids clear of booze and drugs and smokes but no one had spoken up to say, “Hey, those things are out there, we just have to accept it.”

What was the difference?

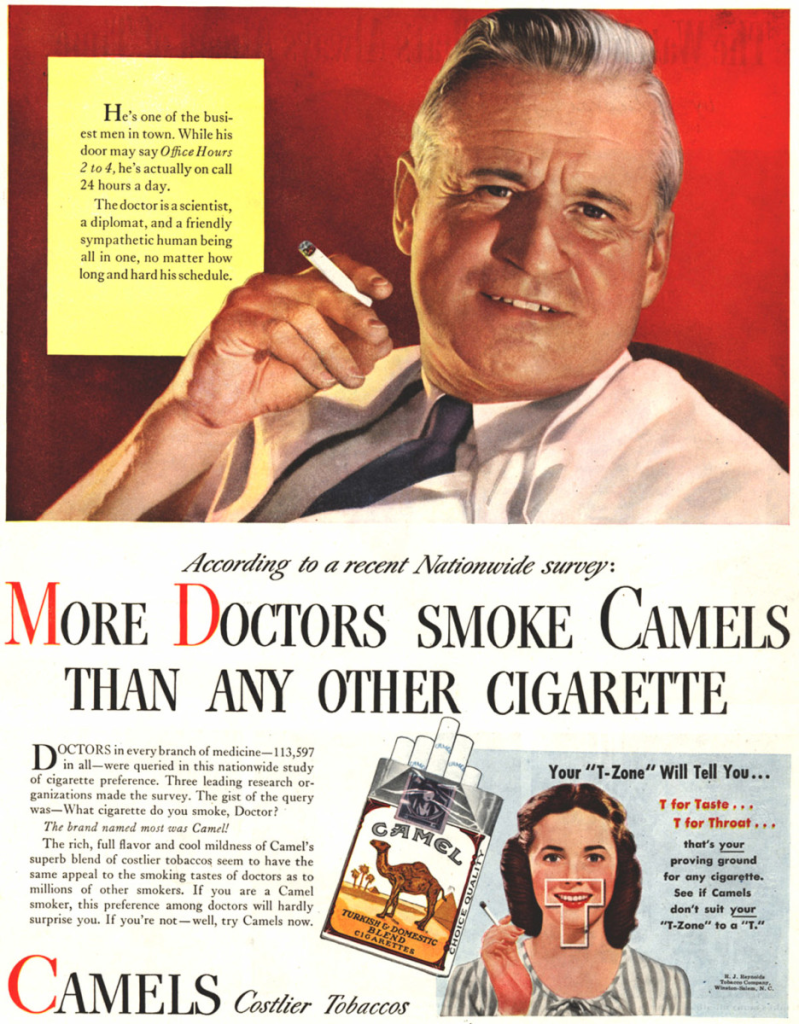

Some day people are going to look back at this era and they’re going to look at our childrens’ use of smart devices and social media the way we now look back at advertisements in which doctors endorsed smoking.

They’ll chuckle and say, What were they thinking?

Lockdowns and school closures had unintended consequences.

So did smart devices and social media.

Is it too late to undo the damage?

And even if it’s not too late, do we have the will to put social media as far out of reach of our children’s little hands as cigarettes, whiskey, and cocaine?

We can’t do this individually: as long as most kids have smart phones and are socializing on them, taking your own kids off is like putting them into exile. It makes your kid the weird kid, the oddball, the outsider—and that’s not doing them any favors either. As parents at the individual level we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

We have to do this together, all of us, as a society, or it’ll never happen at all. It can’t be a right wing thing or a progressive thing, a social justice thing or a Christian thing. It just has to be a thing.

I don’t know what I can to do encourage that kind of change, but I’ve noticed that when I talk like this among other people I no longer get the eye-rolls I used to. I get agreement. Even from child specialists—especially from child specialists.

A lot of people now realize the harm this technology is doing to our kids—I think every parent knows—but no one wants to be written off as a crank or luddite. I’m obviously sympathetic to that: I already told you about my own cowardice.

My hope is that the more people talk about this, the more it begins to bubble up into public discourse and the closer we get to doing something about it.

If you keep doing something after its awful unintended consequences reveal themselves, you can’t really call them “unintended” any more.

We all know this stuff is toxic for kids: let’s stop giving it to them.

Featured Image: Screencap of creepy kids from Village of the Damned.

Well said. As you allude to, with the Corona Lockdown, we essentially removed nearly all natural social interactions and the socialization that happens when kids play among themselves out in the real world, and replaced them with a massive overdose of social media.

And what is social media? A global ,mostly unfiltered access to the inner brute lurking inside every single human being, who was simultaneously handed anonymity, unaccountability, and few if any obstacles to the ability to effortlessly convey every impulse to the world in the same instant it occurs.

I am increasingly coming around to the idea that had you convened the world’s best psychologists, experts in human development and tasked them with creating the most insidious and damaging tool with which to amplify the worst demons of our nature, undermine the civilizing forces that have worked to build sane and competent adults, divide us into ever more fractious groups and just basically screw us up the most, the end result would be social media.

Give the human id a tool to broadcast any whim to the entire world instantly, with minimal filter, make it so small and convenient it can be carried everywhere, have an interface so easy to use that toddlers can master it in minutes, and lean back and watch the humans disintegrate their societies and their minds.

The Devil would look on in awe.

Cat videos are not worth this.

Amen. I wonder how much the world would improve, and how rapidly, if social media simply disappeared overnight. I bet an awful lot of kids would sleep better at night. And school would probably be a better experience when bullying actually required physical effort. (cf. Jordan Peterson’s protesters, who couldn’t be bothered to protest him when he moved his engagements to the early morning hours.) Puberty would still be a hellish trial for most kids, but it would be a hellish trial that ended when it ended, instead of trailing them for all the rest of their days. There’s a lot of modern technology I would have liked to have access to as a kid, but on balance I’m glad there aren’t pictures and videos of my teenaged years bouncing around the ether. Very glad my flirtation with “Youth for Communism,” my experimentation with facial hair, and some of my more tragic fashion choices are stuck in the past where they belong. It’s going to take a very forgiving generation to marry people whose childhoods they can Google…