Do you believe in redemption?

Not as a motif in a superhero movie. Not as a hackneyed cliché in the blurb on the back of a paperback.

Do you believe that an actual human being, flawed and bumbling, can redeem him- or herself through sincere repentance and good deeds?

Could you yourself could forgive, sincerely and completely, someone who had committed some terrible wrong against you? Against your family? Your nation?

It’s one of the great questions we face as human beings, one that we all have to grapple with at different times and in different ways.

But if we truly can’t redeem ourselves, if words like as atonement and rehabilitation and redemption are just made up nonsense words we use to cover an empty space where we feel there ought to be something, where does that leave us?

If, on the other hand, we can redeem ourselves—can, through our actions, if not undo or erase our misdeeds then at least ensure that the good outweighs the bad on the scale of our lives—that would seem to be something important. More than important: it would be something vital and even heroic.

Which is certainly the way we’ve always treated it in our entire cultural inheritance.

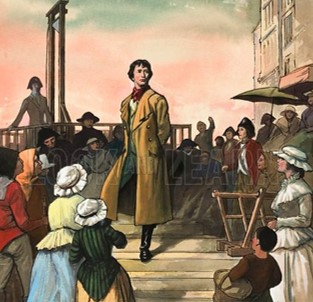

If redemption is impossible, then Christianity goes right out the window, along with a lot of the great literature and art of the world, from ancient Greek tragedies all the way up to movies playing in theatre right now. Sidney Carton’s noble sacrifice at the end of A Tale of Two Cities would merely have revealed him to be a sap and a sucker. Raskolnikov’s sobs at Sonia’s feet toward the end of Crime and Punishment would make no sense at all. And Belle would have been an idiot to have given the Beast a second chance in Beauty in the Beast.

Whether or not redemption is possible, it’s certainly been an ideal throughout our history.

Enter Poul Høi, the foreign correspondent for Berlingske who spent decades misinforming Danes about America:

She got the blame for the sex scandal – but on her deathbed she asked her son to tell the truth, Poul Høi, Berlingske.dk, May 9

Høi’s story is all about Christine Keeler, who died in 2017. Her son, as the headline suggests, is now hard at work trying to set the record straight with respect to his mother.

Who is Christine Keeler?

Here’s Høi’s version:

The history books talk primarily about Keeler’s relationship with War Minister John Profumo. He was a mediocrity who inherited his father’s money and all the benefits of society and ended up as a minister because it was obviously his right. And so it was with his relationship with women.

Conversely, Christine Keeler came from the most miserable conditions and in 1961 was a photo model in London. She was introduced to the married Profumo, and they began a relationship. Normally it would be fine in the political circles of power, because as I said – he just took his right.

But the British intelligence service had warned Profumo that Keeler was also having an affair with the Russian naval attaché, who was possibly a spy. So there was a security risk. But Profumo couldn’t keep it in his pants and continued the relationship, until in 1963 it ended with an investigation in the House of Commons. And thus the affair became public, which was completely unheard of at the time, and a man of power was put to account.

Profumo lied about it all, he denied everything until it was impossible to deny anymore, and his own lie in the House of Commons felled him. He had to retire in 1963 and retired to his mansion and lived the rest of his life on his inherited fortune.

It’s so easy like that: the nefarious mediocrity Profumo twirling his mustache, bedding the poor young “photo model,” getting his comeuppance, and wiling away what years remained to him on the palatial grounds of his estate, kicking at dogs and snarling at sunsets.

Let Mark Steyn set the stage with a little more accuracy (and his usual panache):

It began like a movie: July 8th 1961. An unusually warm evening at a grand country estate. A girl in the swimming pool. She pulls herself up out of the water. She’s beautiful, and naked. A larky lad in the water has tossed her bathing costume into the bushes. And among the blasé weekend guests dressed for dinner and taking a stroll on the terrace one man reacts with more than nonchalant amusement as the girl hastily wraps a towel around her. She leaves with someone else the next day. But not before the man on the terrace has enquired after her name.

It was Christine Keeler. The house was Cliveden, country home of Lord Astor. The name of the fellow who threw away her swimsuit was Stephen Ward, to whom Bill Astor had rented a cottage on the estate for one pound a year. Ward was, formally, a society osteopath and basked in the dingy glow of reflected celebrity: his client list included Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, and, when in town, Averell Harriman, Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra. The man in the dinner jacket so taken by the girl in the dripping towel was the Right Honorable John Profumo, Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for War. The man the girl left with was another guest of Stephen Ward’s, Yevgeny Ivanov.

Miss Keeler was a showgirl at Murray’s cabaret club in Soho. Commander Ivanov was the Soviet naval attaché in London. “Showgirl” was a euphemism for call girl, “naval attaché” a euphemism for KGB intelligence officer.

News of the affair came out, and Profumo did exactly what men of his sort have been doing for all of recorded history: he flatly denied everything, with the Prime Minister at his side.

Then more evidence came out and he could no longer deny it, just as Høi tells us. He faced up to it.

We can take a condensed epilogue from the Sun (UK):

He retreated from public life and dedicated himself to voluntary work, cleaning toilets at the charity Toynbee Hall in East London.

He continued to work there for the next 40 years, only reluctantly taking on a more prominent role as chief fundraiser.

One friend said he “had to be persuaded to lay down his mop and lend a hand running the place”.

This good work earned him redemption in the eyes of many and in 1975 he was awarded a CBE.

Twenty years later he sat next to the Queen at Margaret Thatcher’s 70th birthday party.

His wife stayed loyal to him through it all and also devoted herself to chairty work until her death in 1998.

Profumo died of a stroke aged 91 in 2006.

The facts are all there, but (also as usual) Steyn’s take has a little more poetry:

In 1963, “Profumo” was shorthand for establishment hypocrisy. Across 40 years, he reclaimed the narrative, as a story of shame and redemption, of acting honorably, making the best of a sticky wicket and all the other allegedly obsolescent virtues of his class the sex and hookers had supposedly rendered risible. Had Stephen Ward not thrown a teenage girl’s bathing suit into the topiary, John Profumo would have been noted as the last surviving member of the House of Commons to vote in the confidence motion of May 8th 1940, after the fall of Norway. He was one of only 30 Conservative MPs to join the opposition in declining to support the continued leadership of Neville Chamberlain and thus to usher Churchill into Downing Street. That vote changed the course of the war. But instead his place in history is as the man who saw a call-girl naked in a swimming pool.

The man brought disgrace upon himself and his government. Steyn quotes a limerick that was apparently popular as the events were unfolding in London:

"Oh what have you done?" said Christine.

"You have ruined the party machine.

To lie in the nude

May be terribly rude

But to lie in the House is obscene."

Indeed.

“There was no impropriety whatsoever in my relationship with Miss Keeler,” is the lie Profumo told Parliament.

(Ring a bell? “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Miss Lewinsky” is practically Biden-level plagiarism. It’s a pity Bill Clinton didn’t emulate the rest of Profumo’s epilogue.)

It wasn’t his carrying on a girl that was sharing her favors with a Soviet spy that did in him: it was that lie to Parliament.

So he withdrew from public life. But he did not merely retreat to “live the rest of his life off his inherited fortune,” as Poul Høi suggests.

He repented. He sought redemption. He literally cleaned toilets for a charity.

He didn’t do it for the PR: he sought none. He didn’t do it for the book advance: he wrote no book. He didn’t do it to set the stage for an eventual comeback: there was no second act.

He spent the rest of his life in what appears to have been actual contrition: shame and regret compelling him to do the hard and dirty work of actually making the world a better place, one cleaned toilet at a time.

Did he achieve redemption?

I suppose that’s between him and his maker, but both Queen Elizabeth and Margaret Thatcher seemed to think so.

What matters is that he bloody well tried, and that deserves more than a snotty aside from Poul Høi.

John Profumo showed (eventually) a strength of character that is all too lacking in our elected officials and public personalities, everywhere across the west. His story should be told far and wide. It is better than a cautionary tale: it’s a morality tale.

And god knows it’s not like we’re overflowing with those these days.

Maybe even Poul Høi can be redeemed some day.

But he’s got his work cut out for him.