“What you do to your adversaries today, they will do to you tomorrow.”

It’s such a simple maxim, and so obviously true, and so easily observable in every sphere of human affairs, and at every level of the animal kingdom, that one would expect it to have been said in a thousand different languages across a thousand different cultures.

But I can’t find it.

I’m not saying it’s not out there somewhere: I’m saying it most certainly is, it must be, but I can’t find it.

So instead of opening with a saying from Sun-Tzu or Thucydides or Machiavelli or Dale fricking Carnegie, I have to open with a quote from Greg Nagan, invented on the spot to fill a hole where there ought to have been a maxim. Along with this maxim I offer two things: assurance that words to this effect can surely be found elsewhere, from more respected sources; and an apology for having been too lazy to find them.

“What you do to your adversaries today, they will do to you tomorrow.”

Another way of phrasing that might be:

“The most important teacher of your adversary is you.”

People are adaptive. Life is adaptive. If it wasn’t, we’d still be single-celled prokaryotes, bobbing around in the ocean and eating carbon. When life is presented with an obstacle, it adapts. This is true whether you’re looking at an entire species, a particular culture, or an individual. And it’s true whether that obstacle is an environmental change, a physical barrier, or enemy action.

It’s a truism so obvious that I’ve probably already bored you.

But do you not also find it surprising that no succinct maxim making the point leaps immediately to mind? Have you not also been a little astonished by number of ways in which its wisdom is ignored by people who ought to know better? Who not only ought to, but really need to know better?

Seven years ago, Barack Obama famously declared “I’ve got a pen, and I’ve got a phone.” This was no empty boast about office supplies: he was expressing his intention to use executive actions instead of going through legislative channels to set policy.

This was met with enthusiastic support from the left and predictable resistance from the right. Until Obama left office and Donald Trump picked up the presidential pen and phone: the left and right switched positions immediately.

I’m not picking on Obama and Trump, here: the same attitudinal switcheroos have taken place with every change of executive power in American history. Which is all the more reason you’d expect our political class to be a little more restrained with the enthusiasm with which they support and oppose various tactics.

But they’re not. They forget or ignore the reality that the balance of power changes, and eventually their own metaphorical weapons are going to be turned on them.

We laugh and say, “Well, that sure came around to bite them in the ass.”

Because it always does. Always.

Because what they do to their adversaries today, their adversaries will do to them tomorrow.

If you insist a Supreme Court nomination be handled immediately in the one instance, you’re going to look pretty stupid insisting a Supreme Court nomination be deferred in the other. And vice-versa.

If you change Senate rules to make it easier for your party to get executive branch appointments and federal judges approved, as Harry Reid did in 2013, you’re also making it easier for your opposition to do the same when they’re back in power. (The point is made in an October 2020 Roll Call article entitled “If you don’t like the Supreme Court, blame Harry Reid.”)

My point is, there are cases where foresight ought to be just as keen and penetrating as hindsight. Every change you to introduce to the game is going to be exploited by your opponents. Every new weapon you deploy against your enemy is going to be used against you.

Think of the glorious horsemen of the American plains, whose mastery of mounted warfare is legendary: yet there wasn’t a single horse in North America until European settlers brought them. (It’s a fascinating history in itself.)

Or consider the fact that if Hitler hadn’t been working so hard to develop a nuclear bomb, it’s quite possible his enemies wouldn’t have (my emphases):

The United States government became aware of the German nuclear program in August 1939, when Albert Einstein wrote to President Roosevelt, warning “that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated.” The United States was in a race to develop an atomic bomb believing whoever had the bomb first would win the war.

Robert Furman, assistant to General Leslie Groves and the Chief of Foreign Intelligence for the Manhattan Project, described how “the Manhattan Project was built on fear: fear that the enemy had the bomb, or would have it before we could develop it. The scientists knew this to be the case because they were refugees from Germany, a large number of them, and they had studied under the Germans before the war broke out.” Manhattan Project physicist Leona Marshall Libby also recalled, “I think everyone was terrified that we were wrong, and the Germans were ahead of us.… Germany led the civilized world of physics in every aspect, at the time war set in, when Hitler lowered the boom. It was a very frightening time.”

So whether it’s the use of horses in warfare, a change in parliamentary procedure, or a national effort to build the ultimate weapon of mass destruction, the same rule applies:

“What you do to your adversaries today, they will do to you tomorrow.”

I won’t belabor the point any more. Here we go:

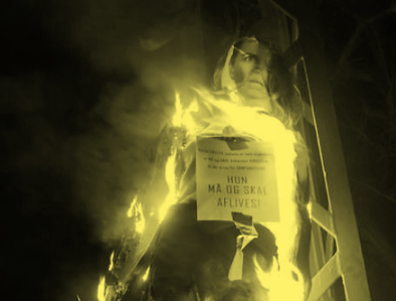

Burning of Mette Frederiksen in effigy shocks: “the most transgressive thing I’ve ever seen in Denmark,” Ritzau news service, Berlingske.dk, 24 January

At a demonstration last night (the evening of Saturday, January 24), as part of an anti-lockdown demonstration in downtown Copenhagen, an effigy of Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen was hung up on a lamppost and lit on fire. A sign taped to its “chest” proclaimed “She must and shall be put down.”

(A note on that translation: to aflive something is to “unlife” it: this is most often used with animals being “put down.” The phrase itself is a variation on the PM’s comments with respect to the nation’s mink population, of which she declared: “they (the minks) must and shall be put down.” But it’s still a call for Mette Frederiksen’s death, which is a terrible and stupid threat to make.)

Here’s opposition party Venstre’s political spokesperson SophieLøhde:

“Simply obscene to string up an effigy of the Prime Minister and set fire to it. Totally fine to disagree politically, but this is below the belt and doesn’t contribute to constructive dialogue and debate.”

And the governing Social Democrats’ own political spokesperson, Jesper Petersen:

“Extremely uncomfortable! Effigy of Mette Frederiksen with the inscription ‘she must be and shall be put down’ was strung up, set on fire, and spit on as part of the evening’s ‘demonstration.’ You have the right to demonstrate, but this does not belong anywhere!”

I agree on the tastelessness and disagreeableness and disgustingness of the burning of any politician in effigy. Of course I agree with their right to do it, but I wouldn’t do it myself and under all but the most exceptional circumstances I wouldn’t want to be part of a demonstration that included such an activity. (I wouldn’t want anything to do with calling for someone’s death under any circumstance where we hadn’t yet descended into total barbarity.)

I certainly understand the universal reaction of Denmark’s political class to this provocative event: it even shows a little foresight, in that any Danish politician rash enough not to issue a full-throated tweet of outrage could probably expect to find themselves burned in effigy in the not too distant future by some other flavor of protestor, and nobody wants to see an angry, masked, black-clad mob burning them in effigy.

But I have a couple of caveats.

My first caveat I’ve already stated, in a way. I said I wouldn’t want to be part of anything like this under anything but the most exceptional circumstances. But my “exceptional circumstances” may not be the same as yours, or Sophie Løhde’s, or Jesper Petersen’s, or the anti-lockdown autonomer.

It’s not hard for me to imagine any given citizen of Denmark, or any other locked down country or state, feeling that ten months of what amounts to martial law does in fact represent “exceptional circumstances.”

My second caveat is more to the point: for the past four years, no “protest” against Donald Trump, against Brexit, or in support of BLM has been criticized with anywhere near the enthusiasm we see here.

In fact, the very day after Donald Trump was elected, he was being burned in effigy on the streets of L.A.

The burning of Trump effigies wasn’t limited to the United States: the Washington Post ran a fairly enthusiastic article in June of 2017 entitled “Photographic evidence that the world is mean to Donald Trump.”

From the article:

And we’re not just talking newspaper-stuffed piñatas. For a president who is often accused of rolling back U.S. influence in the world, Trump has certainly inspired many abroad to great creativity in their efforts to make fun of him.

The article is mostly about burning him in effigy. And the Post is talking giddily about all the “great creativity” in “efforts to make fun of him.”

We’ve had more than four years of that. And just this week, we got this fawning piece in the leftist Guardian about the celebrated Trump diaper balloon being added to the collection of the Museum of London. I realize there’s a significant difference between a burning effigy and a big helium balloon of mockery, but does either belong in anything other than a “Museum of the Symbols of Unhinged Mobs?”

The people around the world burning Trump in effigy, and beating crap out of Trump piñatas, and shooting the hell out of Trump cutouts, and hanging Trump effigies by their necks, had and have every right to make those political statements.

There’ve also been ample calls to kill not only Donald Trump, but members of his administration, and even his supporters.

And the international media had and have every right to encourage them, to run gushing features on them, to praise their creativity and effort. (I guess. I mean, the calls for death strike me as being possibly transgressive in the legal sense: my free speech absolutism doesn’t accommodate actual death threats, but I don’t know where the legal lines get drawn in the U.S., Denmark, or anywhere else.)

So put yourself in the position of someone who believes that ten months of lockdown are “extraordinary circumstances.” You want to protest the policies of Mette Frederiksen, passionately: what signals has the culture around you been sending about the boundaries of political discourse?

They certainly haven’t been signaling there’s anything wrong with the burning of effigies.

So let’s cut to the chase:

I understand the disgust being expressed by the Danish political class. I share their aversion. I’m with them.

But there’s a massive disconnect with respect to this kind of thing internationally, across our globalized western culture, with respect to what is merely noted with a wry wink and what is condemned without equivocation.

To anyone appalled by what happened in Copenhagen last night, but indifferent to (or even supportive of) similar “protests” against Trump that have been taking place all over the world for the past four years:

Who are you to decide who is and is not considered a tyrant or a dictator?

Who are you to say this form of protest is legitimate in this context, or against this person, but not in that context or against that person?

Who are you to say what is and is not transgressive?

When you say, “this political actor is bad and all forms of protest against him are valid expressions of deserved criticism,” what is it you don’t understand about people saying the same thing about someone you happen to like?

Do you wonder how anyone could stoop so low as to call for a Prime Minister’s death and set her effigy aflame, and spit at it?

You taught them this.

You let it become normal because you approved of the target.

They chose a different target, but it was you that gave them permission for the tactic.

And you really should have known better, because as everyone knows:

“What you do to your adversaries today, they will do to you tomorrow.”

UPDATE (25 January): Former Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen (V) was quick to condemn the burning of the effigy, but on Sunday night offered some reinforcement for the premise of my post:

“A member of parliament from Enhedslist amused themselves by burning me at a St. John’s bonfire. Below the belt — an apology is in order. Doesn’t change that yesterday’s burning of an MF-effigy is a genuine threat, which should be cracked down on hard. Doesn’t suit democracy.”

Commenters on Twitter are pointing out the differences between a small and apparently private bonfire on the one hand and a public demonstration in the middle of town on the other. Those differences are real and significant, but my point remains the same: you burn your adversaries in effigy today, expect to be burned in effigy by your adversaries tomorrow.

You taught them how.

The phrase that comes closest, at least that I am aware of, is probably from the Bible:

“for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” (Galatians 6:7 King James Bible)

or the proverb

“Live by the sword, die by the sword” (paraphrase of the line from Matthew 26)

Though these and similar expressions are usually in reference to how God will judge a person, and are not directly expressed in terms of the mechanism of human psychology you are referring to.

Also, the common usage of the Sword line, has traditionally been seen as primarily a renunciation of violence, though given how broadly the Bible uses metaphors, that may actually be too literal an interpretation and it should probably be used in the more general terms you apply, i.e. that the methods you use will be used against you. There is a free idea for a sermon, if any pastor or priest is reading this 🙂

But I like the Boomerang Principle.

Thanks Soren! I thought of the sword one, but it didn’t seem quite right for the reasons you say.

And reaping and sowing isn’t quite the same, also for the reasons you say.

Every action having an equal and opposite reaction doesn’t quite do it either.

Maybe there’s some celebrated game theory philosopher who’s put it succinctly. Or maybe a parenting guru… Dr. Benjamin Spock? (Although hard to think of your own kids as adversaries. Most of the time.)

It’s just a basic and obvious human feature of sentient behavior that there has to be some well-formulated law articulated by someone we’ve all heard of.

“Who are you to say what is and is not transgressive?”

Ah, irony, irony…….

If you’d develop that snark into complete sentences and present your ideas in fully developed form I’d be happy to address whatever criticism you’re driving at.

If you can’t be bothered to take the trouble, why bother saying anything at all?